What is the issue?

- Indian Farmers have been subsidising the nation for a long time despite that they themselves are living on the margins of the economy.

- Elimination of input agricultural subsidies and agri-market reforms would benefit farmers, but it would inherently make food prices costly.

- In this context, “direct benefit transfers” can be initiated to secure the food needs of the poorer sections of the society.

What are the metrics that have guided India’s agricultural policies?

- India’s policymakers have the herculean task of addressing the food security concern of 1.32 billion people in India.

- On the one hand, they need to incentivise farmers to produce more and raise their productivity in a sustainable manner.

- On the other, they need to ensure that consumers (especially the poor) have access to food at affordable prices.

- In order to find a fine balance between these twin objectives, India has followed countless policies that impact both producers and consumers.

- These policy instruments range from:

- Budgetary policies such as input subsidies

- Food subsidies for consumers through ration shops.

- Domestic marketing regulations like Agricultural Produce Marketing Cooperation (APMC) Act, and the Essential Commodities Act (ECA)

- Trade policies such as “Minimum Export Prices (MEP) or outright export bans and tariff duties.

- These policies work in complex ways and their impact on producers and consumers are sometimes at variance with the initial policy objectives.

- So, it is only desirable that policy-making is based on more informed and evidence-based research.

How has India’s agricultural policies fared in the past 2 decades?

- In this context, a recent OECD research has mapped the nature of agricultural policies in India and its impact on producers and consumers.

- The study covered a 17 year period since 2000 and has calibrated about two-third of the total Indian Agricultural Output.

- The report follows standard metrics and includes key indicators like “Producer Support Estimates” (PSEs) and “Market Support Estimates” (MSEs).

Producer Support Estimates (PSE)

- What - PSEs captures the impact of various policies on two components:

- The output prices that producers receive, which is benchmarked against global prices of comparable products.

- The various input subsidies that farmers receive through budgetary allocations by the Centre and states.

- The two are combined to see if farmers receive positive support (PSE) or negative as a percentage of gross farm receipts.

- A positive PSE (in percentage) means that policies have helped producers receive higher revenues than would have been the case otherwise.

- A negative PSE (in percentage) implies lower revenues for farmers (an implicit tax of sorts) due to the set of policies adopted.

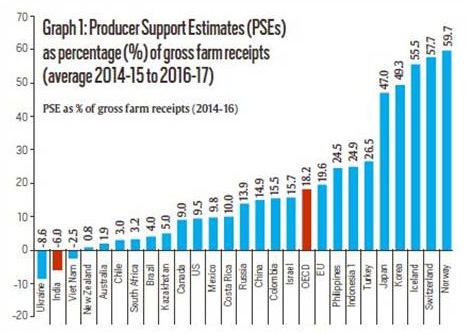

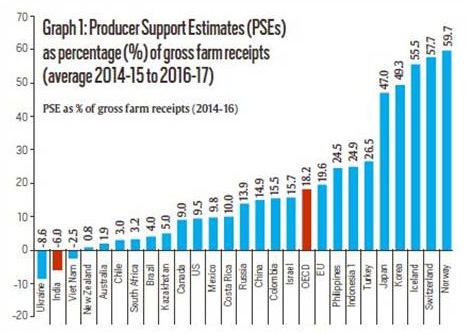

- Trend - The results of the PSE exercise reveal that India’s PSE, on average, between 2014 and 2017 was “minus 6 per cent” of farm receipts.

- Significantly, this is in contrast with most other countries studied which had large positive PSEs - OECD (18.2%), EU (19.6%), China (14.9%), U.S. (9.5%).

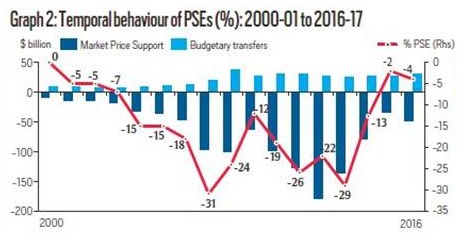

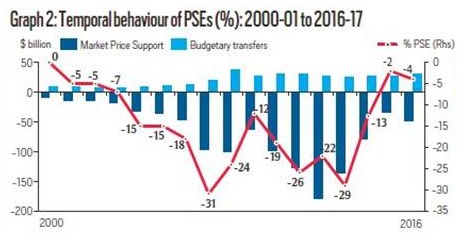

- Also, the temporal movement of PSE (in percentage) for India component parts, over the past 17 years has largely been on the negative side.

- Overall, PSE was negative to the tune of 14% on average over the entire period from 2000-01 to 2016-17, due to large Market Support Prices (MPS).

- This indicates that despite positive input subsidies, farmers in India received 14% less revenue due to restrictive trade and marketing policies.

- The negative PSEs were particularly large during 2007-14 when benchmark global prices were high but domestic prices were relatively suppressed.

What needs to be done?

- Liberalising Markets - There has been a pro-consumer bias in India’s trade and marketing policies, which actually hurts the farmer revenues.

- This needs to change, if farmers are to be incentivised to raise productivity, and build an efficient and sustainable agriculture.

- Firstly, policy change is needed is to “get the markets right” by reforming domestic marketing regulations like “ECA and APMC” acts.

- Promoting a competitive national market, upgrading marketing infrastructure and undoing restrictive export policies are also vital aspects.

- These changes will reduce and eventually eliminate the negative “market price support” that is affecting farmer incomes.

- Subsidising the Poor - Protecting consumers from potential price hikes is a critical aspect that policy makers have to deal with.

- Enhancing the income of farmers would inherently mean that consumers will have to shell out more from their pockets.

- In this context, the OECD report argues for switching to an income policy approach through the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) targeted the poor alone.

- Further, the report states that this can be implemented gradually and would generate better outcomes all round, including for nutrition quality.

- Farm Subsidies - OECD report argues for undoing input subsidies to farmers in India, which is costing the exchequer a massive sum.

- It asserts that farmers would be better off if equivalent amounts are channelled simultaneously towards higher investments in agricultural areas.

- Agri-R&D, extension, building rural infrastructure & agri-value chains, and bettering water management practices are some areas to be considered.

- Structural - As agriculture is a state subject, a greater degree of coordination is required between the Centre and states to usher in big ticket reforms.

- Also, better coordination across various ministries (like agriculture, food, water resources, fertilisers, rural development and food processing) is needed.

- Some policy reforms are already underway, and unwavering commitment is needed to comprehensively overhaul the scenario for the betterment of all.

Source: Indian Express