Why in news?

SC has pulled up various State governments and the administrative side of the High Courts for delay in filling vacancies in subordinate judicial services.

What does the court find?

- The SC Bench had taken suo motu cognisance of more than 5,000 vacancies for subordinate judicial posts, despite more than 3 crore cases are pending in the lower courts.

- There were a total of 22,036 posts in the district and subordinate judiciary, ranging from district judges to junior civil judges, across the States and 5,133 out of the 22,036 posts were vacant.

- The source of the problem lay in poor infrastructure, from courtrooms to residences for judges, and a sheer lackadaisical approach to conducting the appointment process on time.

- The court, in its previous hearing on October, wanted to know if the time being taken for appointments was beyond the seven-month schedule formulated by the top court in the Malik Mazhar Sultan case.

- Under the schedule, the process for recruitment has to commence on March 31 and be completed by October 31 of the calendar year.

- However, the time limit fixed by it from the initiation of the recruitment process till its completion was the "outer limit" and not the "minimum period of completion."

- Hence, if the time taken has exceeded the schedule fixed by this Court, the reasons thereof be furnished by the Registries of such High Courts/concerned authorities of the State where the recruitment is done through the Public Service Commission.

- But the SC noted that there was a mismatch in the number of vacancies, the number of posts for which recruitment process is underway and those still pending,

- Hence it also sought details of the vacancies that have occurred since the current recruitment process commenced.

- The court also sought information on whether infrastructure and manpower available in the different states is adequate if all the posts that are borne in the cadre are to be filled up.

- This was done because there were more than 1,000 vacancies in Uttar Pradesh alone.

- It also discovered that a lack of infrastructure and staff plagued the West Bengal judicial services.

- The Bench found that the recruitment process was under way for only 100 vacancies in Delhi, which has over 200 vacancies.

- It had warned of centralising appointments to the subordinate judiciary as a reason for the delay in filling these vacancies.

How does the appointment happen?

- According to the Constitution, district judges are appointed by the Governor in consultation with the High Court.

- Other subordinate judicial officers are appointed as per rules framed by the Governor in consultation with the High Court and the State Public Service Commission.

- This shows that the High Courts have a significant role to play in lower level judicial appointments.

- A smooth and time-bound process of making appointments would, therefore, require close coordination between the High Courts and the State Public Service Commissions.

What are the concerns?

- Subordinate courts are plaguing with the problem of chronic shortage of judges and severe understaffing of the courts.

- The Supreme Court laid down guidelines in 2007 for making appointments in the lower judiciary within a set time frame.

- Despite that, there is existence of more than 5,000 vacancies in the subordinate courts.

- The SC has pulled up State governments and the administration of various High Courts for the delay in filling these vacancies.

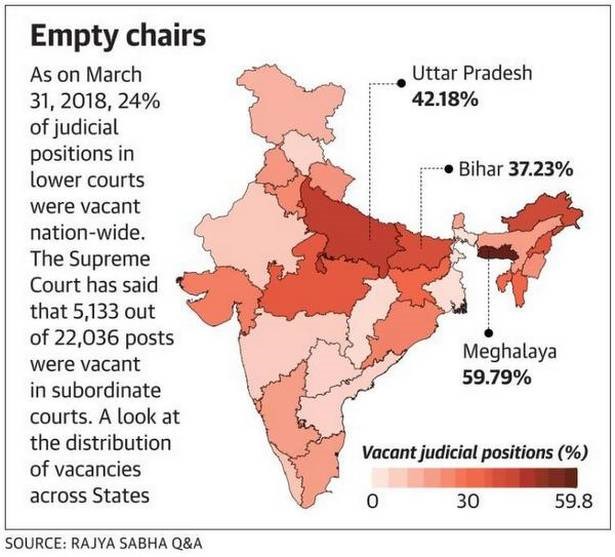

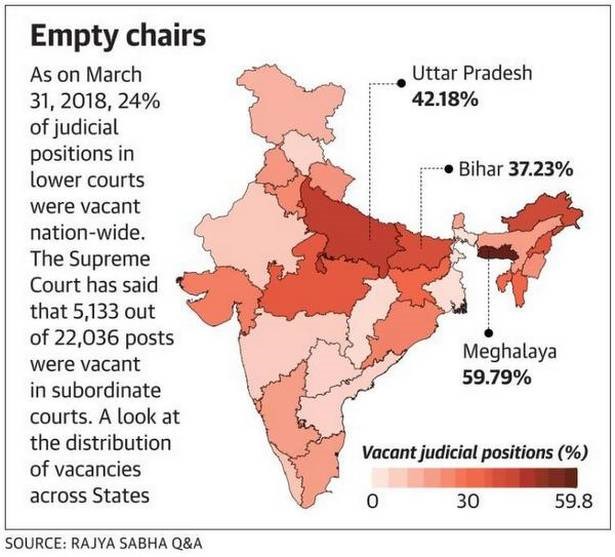

- Answers provided in the Rajya Sabha reveal that as on March 31, 2018, nearly a quarter of the total number of posts in the subordinate courts remained vacant.

- The State-wise figures are also quite alarming, with Uttar Pradesh having a vacancy percentage of 42.18 and Bihar 37.23.

- Among the smaller States, Meghalaya has a vacancy level of 59.79%.

- The possible reasons are –

- Utter tardiness in the process of calling for applications

- Holding recruitment examinations and declaring the results

- Finding the funds to pay and accommodate the newly appointed judges and magistrates.

- Along with that, Public Service Commissions should recruit the staff to assist these judges, while State governments build courts or identify space for them.

- A study released last year by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy revealed that the recruitment cycle in most States far exceeded the time limit prescribed by the Supreme Court.

- This time limit is 153 days for a two-tier recruitment process and 273 days for a three-tier process.

- Most States took longer to appoint junior civil judges as well as district judges by direct recruitment.

- This situation demands a massive infusion of both manpower and resources.

What should be done?

- Subordinate courts perform the most critical judicial functions that affect the life of the common man such as conducting trials, settling civil disputes, and implementing the bare bones of the law.

- Any failure to allocate the required human and financial resources may lead to the crippling of judicial work in the subordinate courts.

- It will also amount to letting down poor litigants and under trials, who stand to suffer the most due to judicial delay.

- Thus the issue should be looked up beyond mere vacancies and the concerned states should take necessary measures to ensure a smooth and time-bound recruitment process for the lower judiciary.

Source: The Hindu