7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

What is the issue?

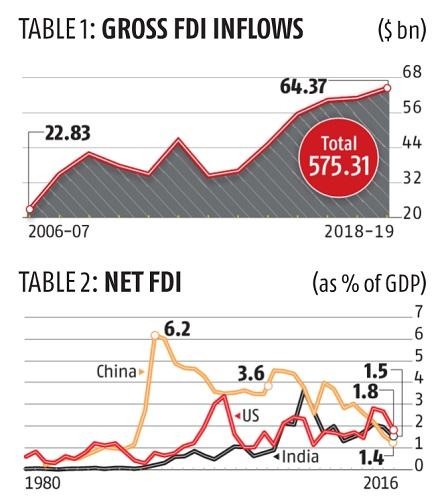

What is the current FDI scenario?

What do other indicators show?

How does India compare with China?

What is to be done?

Source: Business Standard