7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

Why in news?

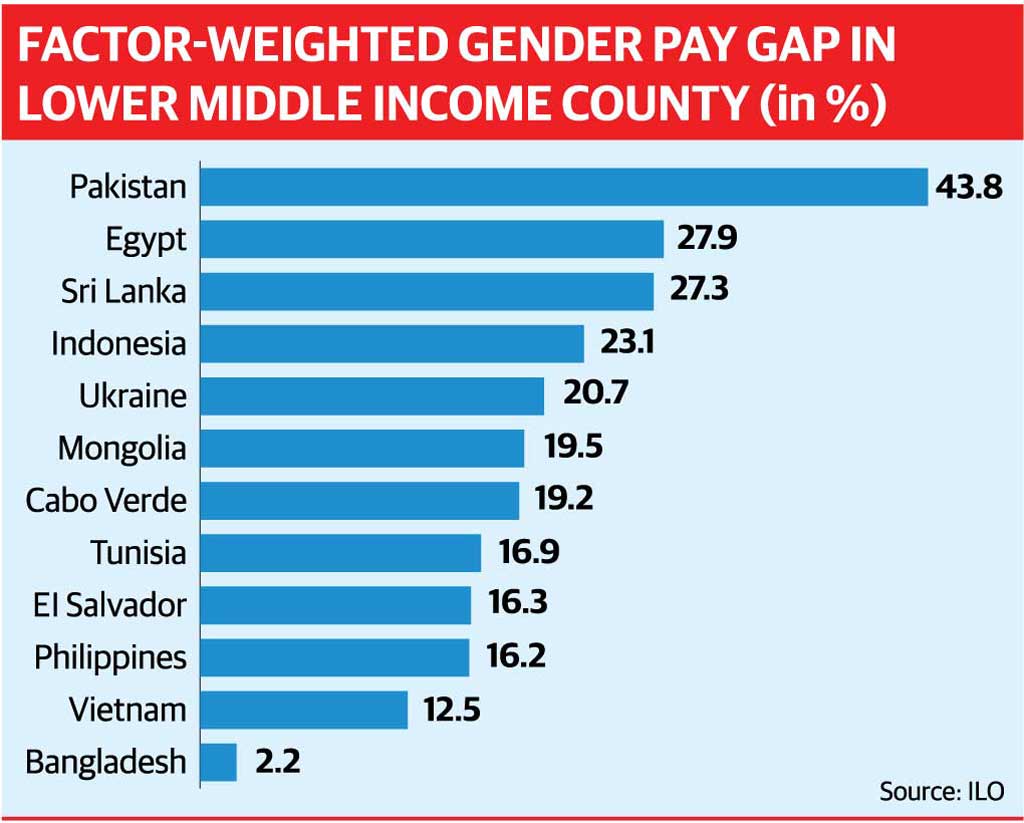

The International Labour Organisation recently released the Global Wage Report 2018/19.

What are the highlights?

What was the driving factor for growth?

What is the implication?

Source: Economic Times, The Hindu