7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

What is the issue?

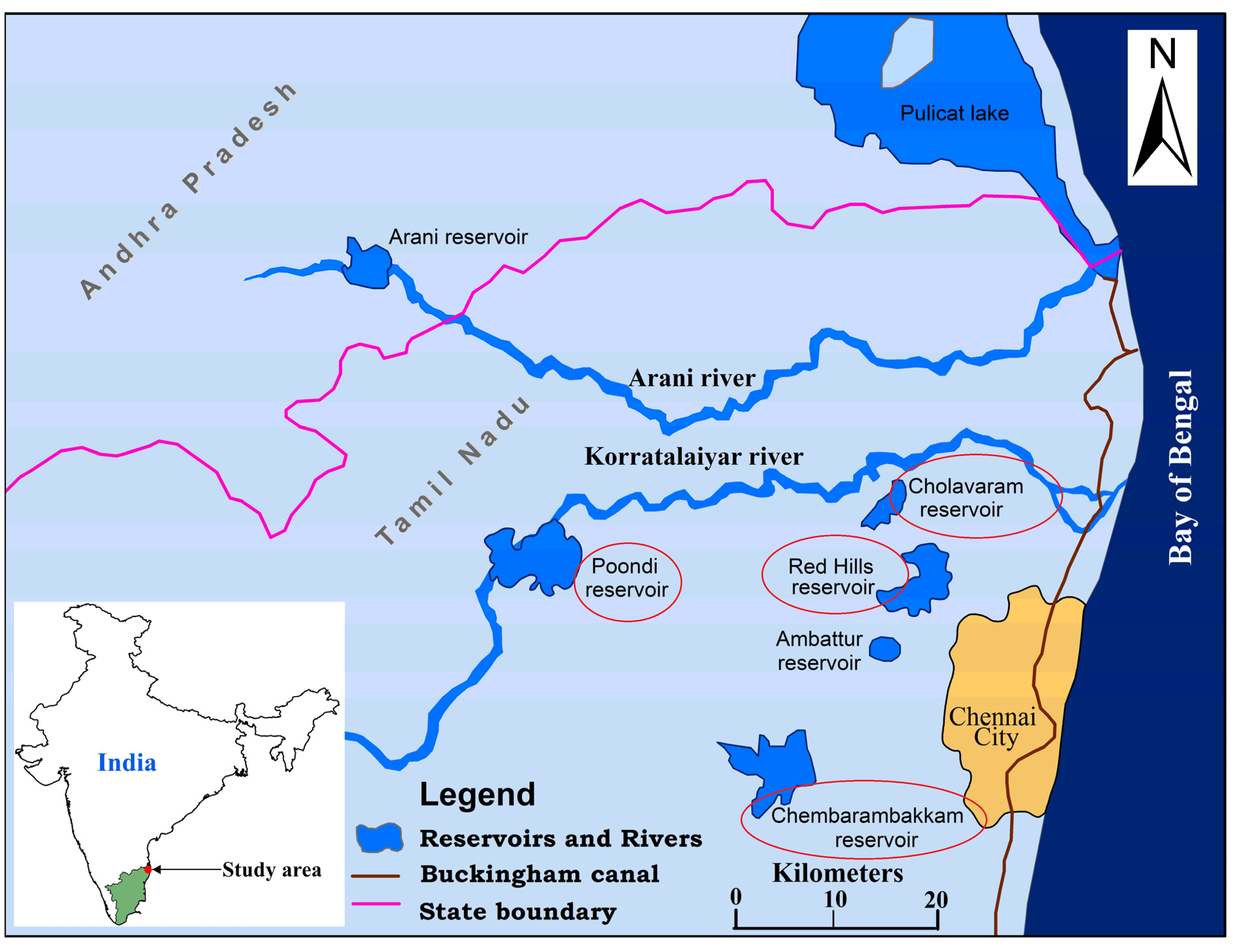

What is Chennai’s current water scenario?

How effective had rainwater harvesting been?

What are the shortfalls in the approach?

How can water governance be made better?

Source: The Hindu