7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

What is the issue?

What are the metrics that have guided India’s agricultural policies?

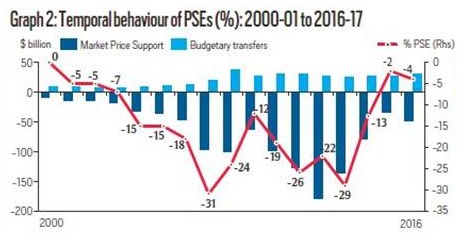

How has India’s agricultural policies fared in the past 2 decades?

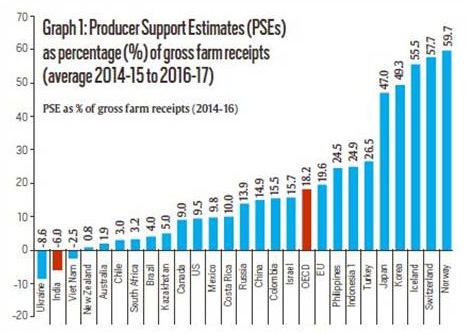

Producer Support Estimates (PSE)

What needs to be done?

Source: Indian Express