7667766266

enquiry@shankarias.in

What is the issue?

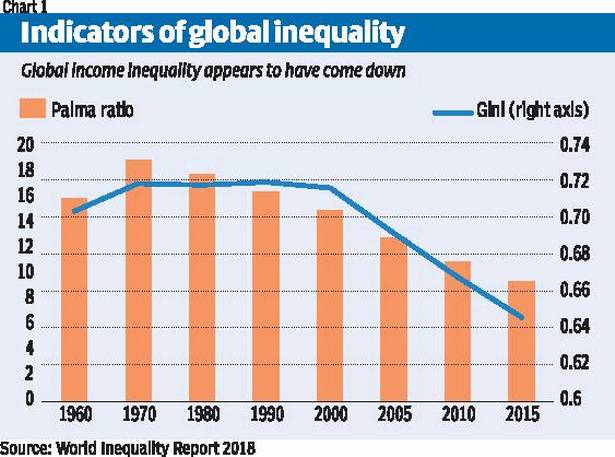

What are the generic inequality trends?

What is the problem with the above figures?

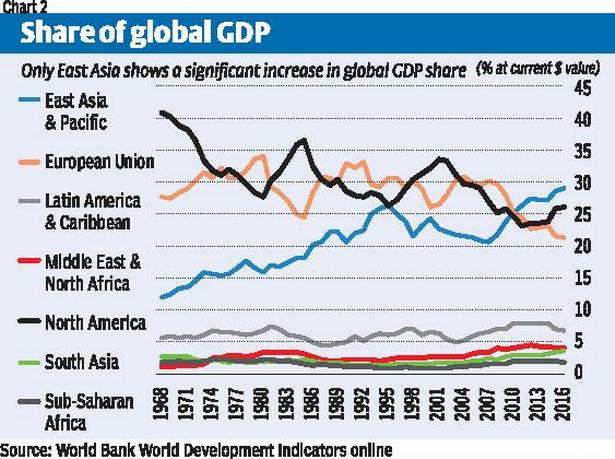

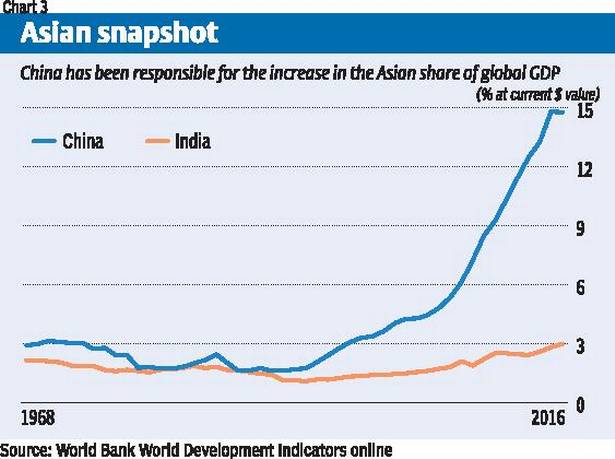

What are the global GDP trends across regions?

What are the income trends within countries look?

Source: Business Line